Mumbles Oysters

Mumbles oysters were once exported to London and Europe, particularly during the Victorian era. Unfortunately, due to pollution levels in the Bristol Channel, the industry died out in the 1920s. Scientists have been leading efforts in recent years to replenish the oyster beds off Mumbles. The oyster trade was once one of the village's mainstays, dating back to Roman times. Between 1850 and 1873, Mumbles' oyster trade flourished. Local fishermen in Oystermouth landed over a million oysters in 1871, which were then transported by train to the London fish markets.

A pair of oyster boats by Edward Duncan 1855

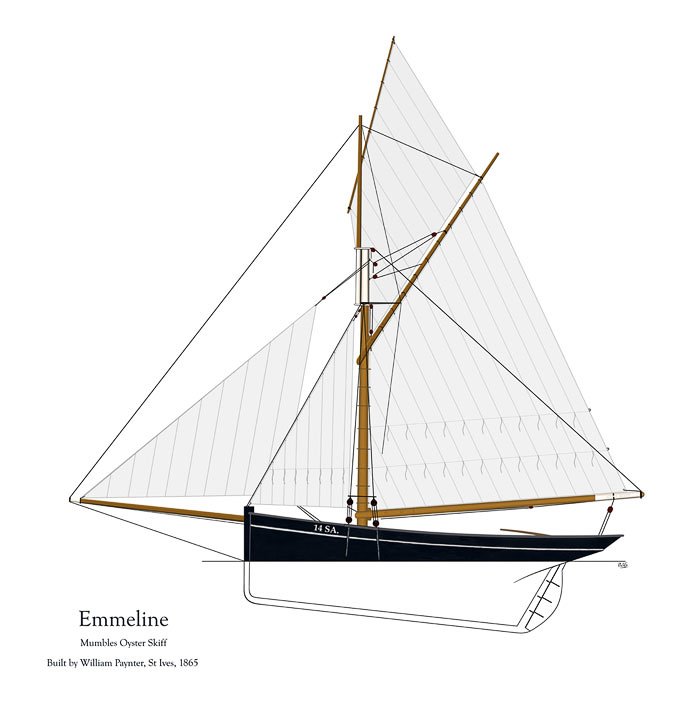

Fishermen used open rowing boats in the beginning, but by the mid-nineteenth century, they were using rigged vessels with a mainsail, a forestaysail, and a jib, which were known as Skiffs. By 1863, there were 780 local crafts and 250 men working during the season. The oysters were now being sold for 9 shillings per 1000 to wholesalers, who then sold them for 7d per score. A single boat could make two trips a day, so a catch of 20,000 oysters was not uncommon. At its peak, 560 men were employed in 188 skiffs, three in each.

Oyster skiffs were outfitted with two Mumbles-style dredges, each with a sharp blade for scraping oysters from the bottom and a four-foot-wide bag that could weigh 508 kilos when full. The exact location of the oyster beds was frequently kept a closely guarded secret. These were in Swansea Bay, between Mumbles Head and Port Eynon.

The Oyster Beds have been given a variety of names over the years, including The Hen and Chickens, Musselly Haul, Itchy Poll, Trashy Ground, Robin's Patch, Middle Drift, and Duck Haul, California, Red Hole, and East India were all located in Swansea Bay, with others located further afield. The Oystermen navigated by using conspicuous landmarks ashore and between Port Eynon and Mumbles, there were some eleven of these markers. However, since they were often closely guarded secrets.

When a skiff arrived at one of the hauls, the two dredges were thrown overboard, and the boat sailed slowly along or drifted sideways if there was a light wind, until the dredges were full. The dredge itself was a bag-shaped net, with the bottom or "belly" made of iron rings and the "back" made of netted cord. The "foot," a wooden bar, kept the dredge's end open and straight, while the mouth was iron, with a scraper known as the "sword" that drew the oysters into the net. Iron "arms" linked the net to the ring to which the dredge rope was attached. The dredge rope, which was about sixty fathoms long, was attached to a winch on deck, and the subsequent winding operation took place.

The decline of the Oyster trade

During the 1920s, oyster fishing died out along the Victorian seaside coastal strip of Mumbles. This industry's decline can be attributed to a number of factors. Pollution of the sea from the River Tawe, a primitive sewerage system in Southend, and overfishing are just a few examples.

When the oysters died as a result of pollution, locals worried that the traditional delicacy would never be revived. Experts now believe the shellfish will be able to thrive on the seafloor within the next five years.

Dr Woolmer, 45, who worked with Cambridge University on the project, said: “The water is so much cleaner now and the oysters seem to be happy down there.

“Not only have the oysters survived the harsh winter last year, but they also grew in size and, crucially, managed to spawn.

“Going forward, it means that the oysters we’ve put in represent a broodstock that could repopulate the bay.

“There is great potential for another wild fishery and that could happen in the next five years.”

The return of the delicacy has been welcomed by the annual Mumbles Oyster and Seafood Festival, which attracts 8,000 visitors each year. Every year, festival organisers import 3,000 oysters from England, but this year will be the first time they serve local specimens.

Horsepool Haven 1850s

The Horsepool was a natural harbour surrounded on most of its seaward side by a sandbank, bordered on the other side by the roadside and extending from near the White Rose Public House to The George Hotel. On a normal high tide, the sea would rise up over the sandbank, across the Horsepool, and all the way to the road's edge. The Oyster Men and their skiffs would set sail from here to dredge for oysters in Swansea Bay and down the Bristol Channel. Since the 17th century, fishermen have anchored their boats along the coast as far south as Southend to seek shelter from storms. With the growth of Mumbles as a tourist destination in the 1890s, the Swansea Improvements and Tramways Company decided to extend the Mumbles Railway line from the Castle Hill Terminus at Oystermouth, out across the Horsepool to the Parade Gardens, and then to the other part of their development—the new Pier. As ballast from Cornish ships was used to fill the now-defunct Horsepool, the soon-to-be-enclosed area became known as the Ballast Bank. The ships would then return to Cornwall with Mumbles Limestone on board. A funfair was quickly built on the site, which is now home to the tennis courts, Bowling Green, Promenade Terrace, and Cornwall and Devon Places. Prior to the 1890s, the tide would reach where the main road now is. The loss of the natural harbour prompted complaints from fishermen, and in response, the railway company constructed a wooden breakwater or groyne to protect their boats.

As compensation for the loss of their harbour, the Railway Company built a wooden breakwater on the shore near the Antelope to provide shelter for the skiffs. Unfortunately, the Oystermouth U.D.C. refused to maintain it, and when Mother Nature took her toll, it quickly fell into disrepair and was swept away in a gale in September 1904.

Credits and References

A History of Mumbles: